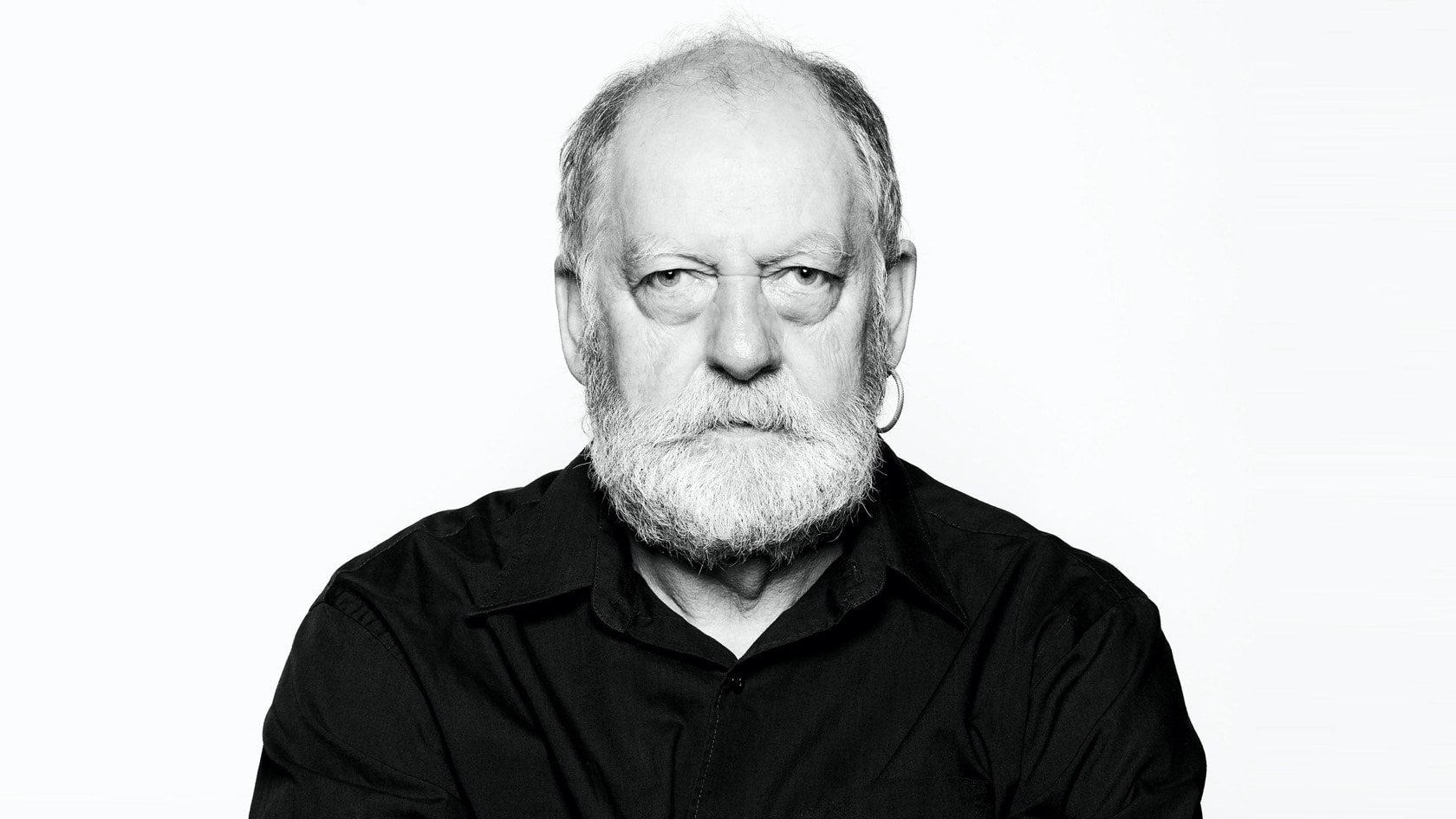

Denis

Michelangelo, Rubens, Rembrandt, Géricault.

He speaks of them as friends, rivals, brothers.

As he lays paint on canvas and sculpts clay, they are his masters and his inspiration.

In Quebec, he is one of the last survivors in the lineage. Seeing his works’ striking realism, painstaking attention to the universal human condition, and rich precision of detail is like catching a glimpse of a painting in the Louvre or a sculpture in a great cathedral. It’s in the details of musculature, the glint of bronze.

Denis is a portrait maker.

“Painting as I understand it was invented in the fifteenth century. So there were 450 years of innovation, of evolution, leading up to Bouguereau.

The painters of the European academies developed a technique they called la demi-pâte that produced an incredible effect. But today it’s a lost art. Nobody knows about it.

Painting in this style requires an understanding of chemistry and the physics of materials. This creates a relatively smooth medium that brings out the translucent quality of oil paint.

It’s a far cry from just laying down brushstrokes, one after another.

And it’s an extremely difficult, temperamental technique to master.

The artist must adapt to the demands of their medium to achieve what they want. It takes a sophisticated understanding of the delicate qualities of the finish, and of their materials. And it’s hard to explain without having the original in front of you.

No reproduction can capture the luminous effect of oil paint.”

In every line he draws and every word he speaks, Denis’s passion shines through – passion for his noble and exacting medium, and the great skill, perseverance, and patience it demands. Quite simply, his passion for the craft.

“The task of the artist is to never stagnate.

We have to continue educating ourselves.

Push ourselves beyond saying just, ‘I like it,’ or ‘I don’t like it.’

The degree of technical difficulty matters also.

What I find myself attracted to, above all, is virtuosity.”

“I came into this world with a pencil in my hand.”

As he speaks in a gentle, serious voice, remembering his childhood, Denis’s bright, curious eyes turn boyish.

“My father worked in a paper mill, and he would bring home big pieces of newsprint for me. He’d lay them out on the floor, and that was the last he would see of me. I drew non-stop.”

This love of drawing was shared between father and son.

At night, before he went to bed, he would leave a sketch on the table.

In the morning, when I got up, I’d see his drawing, and try to copy it.”

The work of the European masters found its way across the great gulf that separated Italy and France from Denis’s native Shawinigan, and into the youthful hands awakening to the joys of art.

“My parents only had one art book – a beautiful work, written by René Huyghe, who was a conservator at the Louvre Museum and an important twentieth-century art critic. He’s someone I really admire.”

We can easily picture young Denis spending hours leafing through the book – analyzing sketches and techniques, imagining the age of those grand masters of portraiture, and aspiring to learn from them. He began looking for a place to hone his craft, but soon hit a dead end.

“At school, my friends and teachers were fascinated by my talent.

But there was no place that taught the academicist style. And really, there still isn’t.”

Denis undertook to teach himself, helped by books and the advice of an uncle knowledgeable in graphic design and painting.

“I had to wait until CEGEP to get a chance to study sculpture. I started in 1971, right in the middle of the Quiet Revolution. The old Schools of Fine Art had closed in 1969. In their place, advanced art education would consist of faculties of Visual Arts and Sculpture. Anything resembling academicist drawing was just gone, off the curriculum.

And there I was, dreaming of Michelangelo.”

Not to be deterred, Denis went on to university where he audited the live modeling classes. But the teaching philosophy of the time was firmly anchored in a conceptual approach at the expense of the technique he so desperately sought.

“Even with two models posing there, the instructor would say: ‘Don’t look at the page, take a thick paintbrush and ink, analyze the models and let yourself be inspired.’

I wanted nothing to do with that. I drew. And again and again she would come up behind me and say: ‘That’s not how we do it nowadays.’”

Stigmatized for his devotion to an “outdated technique,” yearning for a kind of knowledge that seemed nowhere to be found, Denis quit his formal art education for good.

“The writings were still there, the artists’ works were still available, so I did some digging for descriptions of the kind of discipline used in teaching through history.

Working from that, I designed my own classes, alone.

Drawing, anatomy, life models, and then oil-painting technique.

The craft.”

Today Denis can look back philosophically on the institutional inflexibility he encountered, and advocate for the freedom to create, independent of latest trends.

“With Malevitch’s White on White, in 1918, we reached the endpoint of something. The artist can do what they wish. The freedom is there. As it should be.”

In the course of his research, Denis heard about the portrait painters who set up stalls on the streets of Old Quebec City. He set out for the provincial capital.

“I came to take a look. I gave it a try, and I loved it.

That’s how I spent the next 25 years.

And it was there — surrounded by thousands of portraits — that I developed my expertise.

I was hooked.

It pushed me to change and evolve.”

This gig gave Denis the free time to fine-tune his art practice and continue his self-directed learning.

“I would spend my summers painting portraits in the Old City. The rest of the year, I continued my research into drawing and painting.”

As the years went on, Denis developed a fluid, dynamic signature style, creating portraits of an almost photographic realism that still bore the unique imprint of the paintbrush or pencil. He dedicated himself to a representational style that celebrates both a personal symbolism and the qualities of the medium itself.

While he tends to steer clear of the art world, where galleries and dealers pigeonhole artists into single genres, his work was gathering attention.

Commissions from parliamentarians and clergy brought his paintings onto the walls of Quebec’s National Assembly and the Archbishop’s residence.

“There were times when I struggled.

During the holidays, I’d often rent a booth in some mall, like Place Laurier.

But still, when springtime rolled around I’d be three months late on my rent, with my electricity cut off.

But the seasons would turn, and my fortunes would improve.

Of course, I wasn’t exactly living a frugal life, either!”

Denis laughs about it, rubbing together hands coarsened by paintbrush and clay.

A turning point came: the 1984 William Bouguereau retrospective at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

“I had never heard of him.

I left that exhibition furious. Furious because I’d been lied to.

I’d always been impressed by the classics that I found in books: Rembrandt, Rubens… The ones that everyone admires.

But I’d never heard of the nineteenth-century academicists. Most art history just skips over them. I felt as if the very thing I needed had been hidden from me.

You hear them mentioned in passing. Oh, yeah, the Impressionists won their battle against Academicism. But they never went so far as to explain what Academicism was.

It was wiped from our memories for the entire twentieth century.”

A long-held vague desire turned into an urgent necessity: this lost knowledge had to be taught again. It must not be lost forever. What began as a portrait workshop would grow into the Académie des beaux-arts de Québec, which Denis founded in 2008.

“They say that we start by learning from our teachers, then from our colleagues, and finally from our students.

When you teach, your work is ongoing, you’re changing yourself. You have to be patient. You have to be persistent. My academy, for example, took a while before it got off the ground.

Today, I’m proud to see the next generation coming up: Rosalie, Geneviève.

It still feels fragile, but I’m proud of having started it.”

Transmit know-how, not opinion: that’s Denis’s watchword.

“I’ve fought prejudices all my life. To topple them, nothing works as well as education and information.”

“Sculpture has always been secondary for me.

A few years ago, I decided it was time to change that. Especially since everything we learn in painting and drawing has a practical application in sculpture.

There’s a saying, ‘Making a sculpture is like making a thousand drawings from every imaginable angle.’

Financially, I’m doing a little better now, so I can throw all my energies into it. And I have some collectors, patrons who are ready to invest in my art.”

Though he may have an eternally youthful curiosity, Denis admits that he’s beginning to feel his age.

“I developed tendinitis from painting.

And there’s no treatment for that, except stopping the repetitive movements.

And then, doing sculpture, I developed arthrosis in my thumbs.

So I go back and forth between painting and sculpture. They’re different kinds of pain, so it works out pretty well.

It’s too bad, though. Because I think there’s a lot left for me to do in painting. And in sculpture, well, I’m just getting started.

And the time I have before me is limited.

I try to make the best use of what time I have left.

I’ve still got so much to do, it would take two thousand years to do it all.

But that’s not what I have.”

Denis may regret not having Michelangelo’s good fortune of apprenticing in an artist’s studio at eight, mastering the techniques at a young age.

“My apprenticeship wasn’t finished until I was nearly forty. Michelangelo made his David at twenty-five.”

But he looks fondly on the road he’s traveled, proud of staying true to himself and his journey.

And looking at him now, serene and determined, it feels like he’s nowhere close to finished.

His art is rising to new heights.

He’s breathing new life into ancient knowledge.

To pass it on and inspire others, so that nothing will be lost.